What is the Witch-Craze?

Whenever the European Witch Craze brought up most people scratch their heads and ask “what’s that?”. This first newsletter is aimed at laying out the craze for you. To really understand the course, you need to understand what the Witch-Craze is.

During what historians call “the Early-Modern Period”, a time period roughly between 1500-1800, there was a holocaust of sorts. While there is no real estimate, because of the poor record keeping of the time, but historians estimate the number of executed witches between 60’000 and onwards up to nearly 1 million in some estimates. This was a continental event in Europe, affecting every nation of the period, spreading from Germany and Austria, through Italy, France, England, Scotland and onwards. Really anywhere people lived in Europe during this time, there was a chance the witch-craze reached their town or village.

Historians have been so varied on their interest of the European Witch-Craze, or European Witch-Hunts. Some study the victims, a group which tended to be women in nearly 80% of the cases. Historians may study regional witch-hunts, as each country had a unique set of circumstances. Some historians study the beliefs, or the written works that helped spread the craze, this is a field that most modern historians would call Intellectual History. If the Witch-Craze is your forte you can study it as a part of religious history, cultural history, gender history, women’s history, social history and any other history you can think of. While most people would think there’s no way this is a legitimate interest of professional historians, it is a very rich field in terms of scholarship, and academic writing. In graduate school, while talking about my interest in this field, an older student told me to “look into a field that is more serious”. I remember feeling so frustrated but I later articulated to him the importance of this study. Through studying this we can study women’s history, the cultural and social trends of the day. We can see what people were writing about, and talking about, while also understanding conflicts between people through this study.

Just know that the Witch-Hunts did happen, they consumed the lives of many Europeans, and they represent a very chaotic moment in history. My aim with this newsletter course, it to break down many aspects of the witch-craze. Characters will be looked at as well as primary sources, and victims of the craze. We will talk about the different regions of the craze, and the debatable causes of the event. The foundations of the craze will be discussed in this newsletter today. What do I mean by foundations? I mean the things that needed to happen in order for the witch-craze to occur. A certain set of circumstances that were crucial to the expansion of the craze. If you enjoy my newsletter today, please subscribe as we will carry on for, likely what will be, the next several months, before we move on to a new topic.

A Witch-Hunter who changed the game.

There always has to be one, right? There is always the one person who has to get the ball rolling. This was certainly true in the 1400’s. While witches were widely accepted as threats, and sometimes productive members, of European society, the angst against them needed to spread. The written word was now an option to help spread things around. In 1440 Johannes Gutenberg invented a groundbreaking device, the printing press. Books were now accessible to many, and many copies could be made with minimal effort. Gone were the days of monks etching fancy letters in their illuminated manuscripts. Instead, the written word could be stamped out with the crank of a lever. This would birth a new phenomenon, the bestseller, and one of the earliest bestsellers was a witch-hunting treatise known as the Malleus Maleficarum.

That bestseller was written by a guy named Heinrich Kramer, or sometimes known as Heinrich Institoris. Kramer embodies a perfect segue into the foundations of the witch-craze, meaning if you know some about the man, then you can understand why the witch-hunters were so successful. Kramer became something known as an Inquisitor, which are members of the Catholic Church, created to combat heresy. The Dominican Order, of which Kramer was a part of, was established in 1216. The purpose of the Dominicans was to break away from the walls of the convent, to spread God’s word in the world, kind of like an early evangelical. Kramer, born in Schlettstadt, in 1430, a town in what is now Alsace but in 1430 was part of the Holy Roman Empire. Just like every red-blooded boy, Kramer wanted to be a Dominican Monk when he grew up and joined the order in his hometown. For the day he received a top-notch education, learning not only religion but physics, philosophy, science and metaphysical philosophy. Kramer’s education is important to understand, because the average early modern European lacked the ability to read or write. The religious leaders of society fell into the category of educated elite and thus had tremendous power.

During Kramer’s rise to prominence in the Catholic Church, which we’ll cover here shortly, he lived in an era of extreme paranoia. Don’t ever let anybody long for the good old days of the early modern Europeans because life was tough. War, famine, an ice age, disease and religious tension all diverged to become a large stressor for church leadership. A growing concern that the Devil himself was roaming the earth, targeting the humanity of Europe became central to the Catholic thought of the day. One of the largest threats to expanding the Devil’s evil was heresy. For those outside of the church lingo, heresy is basically the equivalent of doctoring the teaching of the bible to manipulate people. Manipulation, or denial is the main focus of what constitutes heresy, and this was a threat because heresy could spread ideas like wildfire. The Catholic Church created an elite force of heresy warriors, known as the Inquisitors, to combat heresy. Since heresy was so incredibly terrifying, the Catholic Church allowed Inquisitors to combat this threat at all costs. This meant your inquisitors could torture and execute perceived heretics. This also coincided with an era where you were guilty until proven innocent, and the person bringing charges against you didn’t have to be held accountable. This is during a time where your church leaders were your judge, jury and executioner.

Kramer was highly ambitious, and nobody hated heresy more than Kramer did. It was his obsession. He stopped at no ends and was known for his fiery moments of extreme emotion. Once the man became so emotional, he did the unthinkable, he slandered the name of the Holy Roman Emperor. Emperor Frederick III didn’t take too kindly to the speech of this Dominican rockstar, so he had Kramer imprisoned! The Dominican order had their golden boy released from prison, but he continued to bump heads with others in the church.

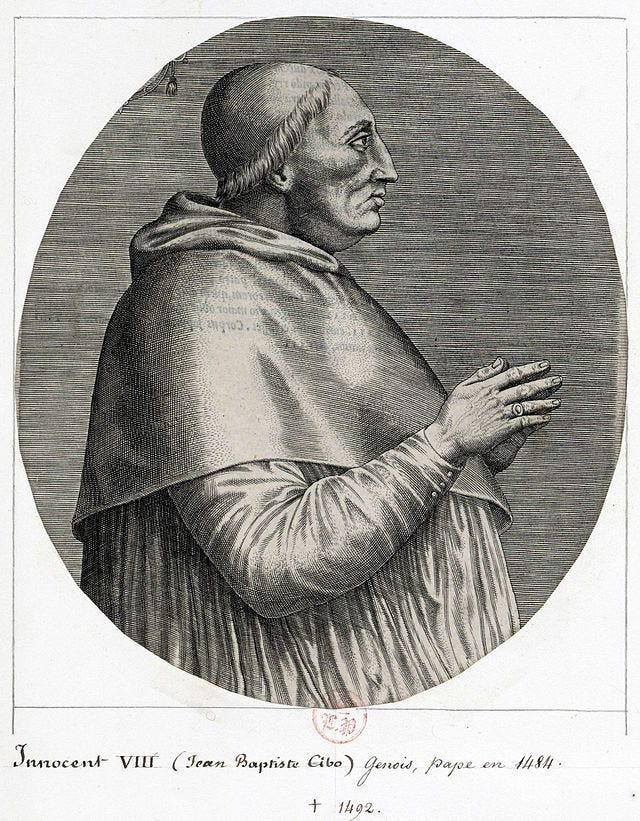

While heresy was the focus of Kramer’s early career, the next threat to the Catholic Church rose to prominence, witches. By 1480 Kramer started to worry about witches. As an Inquisitor, Kramer had a unique situation where he wasn’t pinned down to just one town, or city. With the freedom to travel and sit in on various town trials and listen to accusations all over the empire, he started to hear more accusations of witchcraft. In 1484, after a series of sermons touting the dangers of witchcraft, Kramer took a letter to Pope Innocent VIII, asking for the opportunity to become a witch-hunter. The Pope signed the famous Summis Desiderantes (if you were there, you would have thought it was famous) a edict recognizing the existence of witchcraft, the existence of witches and he gave the church power to hunt witches.

The Summi put the church on the offensive to combat the heresy that would later be known as witchcraft. The first few lines of the order states:

that all heretical depravity be put far from the territories of the faithful, we freely declare and anew decree this by which our pious desire may be fulfilled, and, all errors being rooted out by our toil as with the hoe of a wise laborer, zeal and devotion to this faith may take deeper hold on the hearts of the faithful themselves.

Further down the list on the order, is where the church dips into actual witchcraft. While the name “witchcraft” or “witch” isn’t explicitly used, but I will touch on that in a second here. First just read the quote:

many persons of both sexes, heedless of their own salvation and forsaking the catholic faith , give themselves over to devils male and female, and by their incantations, charms, and conjurings, and by other abominable superstitions and sortileges, offences, crimes, and misdeeds, ruin and cause to perish the offspring of women, the foal of animals, the products of the earth, the grapes of vines, and the fruits of trees, as well as men and women, cattle and flocks and herds and animals of every kind, vineyards also and orchards, meadows, pastures, harvests, grains and other fruits of the earth; that they afflict and torture with dire pains and anguish, both internal and external, these men, women, cattle, flocks, herds, and animals, and hinder men from begetting and women from conceiving, and prevent all consummation of marriage; that, moreover, they deny with sacrilegious lips the faith they received in holy baptism; and that, at the instigation of the enemy of mankind, they do not fear to commit and perpetrate many other abominable offences and crimes, at the risk of their own souls, to the insult of the divine majesty and to the pernicious example and scandal of multitudes.

Kramer, and his colleague who later had his name listed as co-author of Malleus, Jacob Sprenger, are listed in the order. The Pope sent Kramer, and his cohort on a mission to save those at risk of eternal damnation, by way of witchcraft, and at all costs were they to end the threat.

Kramer took this to heart, and in the summer of 1485, he decided to intervene in the region of Tyrol, Austria (modern-day Austria), where he hung around Innsbruck, the capital of that region until February of 1486. He certainly made himself known. He ran a publicity campaign, telling anyone who knew of any possible witches, to rat on said witches to the church. To add to the fire, he preached to everyone in the city, telling them all about the threat of witches. Getting everyone fired up in his preaching campaign. The summer of 1846 he indicted over 50 witches, condemning them to death. Until February of 1486, he was obsessed with weeding out the heretics from Innsbruck’s society, eventually getting booted by the bishop of the city. It didn’t matter, he had all the information he needed to write his book, the Malleus Maleficarum.

How Kramer got his evidence further shows the confirmation bias of these Inquisitors. Inquisitors were allowed to rid the world of heresy at all costs, and this meant torture for most. The whole thing is screwed up by our modern standards, especially the way these guys got their evidence. Essentially Kramer would torture witches until he heard what he wanted to hear, and then go “you’re a witch!”. His sample of real-world witches were asked leading questions, while being tortured, until they confessed to their crimes and were then executed. What would a leading question be? Perhaps one question would be “you have had relations with the devil, haven’t you?” and these women, and sometimes men, were desperate for the torture to stop and would give in. Once Kramer got what he imagined a witch was, from his first victim, he would torture the others until they gave him the same answers, and then he would mark down their confessions. As the list grew, the idealized witch grew with it.

Kramer really got everything he needed from the one run through Innsbruck, to write the Malleus. That is exactly what he did. While Sprenger’s name is on the book as co-author, historians differ on the role he even played. Some doubt that Sprenger was involved, at all. Kramer’s importance as an actual witch-hunter really comes down to the book, which is the next part to discuss. Kramer lived until 1505, living out his life as a devout monk, desperate to combat heresy.

The Malleus Maleficarum as the foundation for Witch-hunts

The book Kramer published in 1487 laid out the foundation for witchcraft, and what to look for. Remember above, in the Summis Desiderantes, how witches weren’t explicitly mentioned? Well, what they were mainly accused of, is. That is dark magic, or Maleficium. Folk traditions in Europe, for centuries, allowed for beneficial magic, and the counterpart to that was the dark stuff. This could be anything. It could be someone made your corn crops die, or your child get sick. Anything you can imagine that would be taken as a slight, could be seen as dark magic. This was known about sorcery at the time, and once this sorcery was tied into heresy, it became a church issue.

Kramer’s book set the way for people to rid the world of these heretics, but there was more to it. A witch, explicitly, was guilty a far more than simple dark magic. The worst crime of all, was a relationship with the devil, often a sexual relationship. This was foremost the reason why these witches could channel the dark magic. The Devil allowed them to do it. Through a sexual relationship with the devil, they were able to form a pact with him. Many historians have debated the reason for this sexual pact, but many state that during the Early-Modern Period, women were often seen as having insatiable sexual appetites. This went directly against the teachings of the church, because lust is bad, right?

During this time period, the Devil working in the world was a genuine threat. He was capable of inserting himself into the daily lives of people, and actively worked in stealing God’s people for his evil activities. This is ultimately what made witchcraft, heresy. Working directly with the devil, not only for use of harmful magic against the children of God but working in order to convert as many people as possible, to the dark side. That’s where major aspects of the Malleus come into play again. The Sabbat, as it was known, was a gathering of other witches. Usually this happened at night, and as a nocturnal activity, it allowed for women to sneak out and commit themselves to the dark work of the Devil. This was part of a recruitment strategy for the Devil, allowing for more witches to join his team. This gathering is where witches did their evil acts, often eating babies, and engaging in sex outside of marital confines.

Kramer used his evidence, of other witches partaking in these activities to corroborate his theory. Throughout the entirety of the witch-craze, as we’ll see, witches throughout Europe were accused of these acts.

What is the importance of this book? Why is it such a big deal? It’s one of the earliest moments where the beliefs of the commoners, tied into the beliefs of the educated and elite members of society. The educated people were able to turn the commoners into crazed witch-hunters. Many Europeans grew up around those who worked in some kind of sorcery, whether it be divination, healing, love-magic etc. The elite, like Kramer, were able to turn the minds of these people, where they saw these citizens as a threat to their world. This happened during a time of tumult. War, plague, famine, weird weather events and more occurred during this moment where the Devil was a threat on earth. Kramer’s book was circulated enough to reach the hands of other educated Europeans. Not just church members, but the wealthy and educated members of any town, or city. While his book wasn’t the last witch treatise published, it is certainly seen as the most influential by most historian.

To Summarize:

The witch-craze needed a foundation to begin. It needed the beliefs of the elite, to tie into the beliefs of the common person. Someone needed to outline what to look for in your local witch, and the work of Kramer gave them that. The religious leaders of the day were trusted with the souls of the people, and many doubted the church would steer them wrong. The foundations of a craze like this come in the form of an intellectual foundation. While Kramer’s book was published well-after the beginning of widespread witch-trials, he popularized the concept and it spread. Kramer would be the first of many to publish popular books on the subject.

Historiographical note:

It is important to understand the historians, and their arguments. This is part of what professional historians do. While primary sources are king, the arguments of other scholars usually fuel the conversation. This week I based most of the writing off the work of Hans Peter Broedel and his work The Malleus Maleficarum: and the Construction of Witchcraft- Theology and Popular Belief. This is great introduction into Kramer’s work and study of the intellectual origins of the craze that followed. If you would like to check out the work, you can read it here for free. It is archive.org so you will need an account to borrow, but the accounts are free. I highly highly recommend you get an account and check out the site. There are over 34 million free, scanned books on there and almost any book you can imagine, especially academic, is on there.

Now next week we will move on in our witch-craze journey and examine the victims of the craze. Until then, thank you for checking this out!